Plague Threatens Aberdeen: 1498-1513

Plague had broken out in Scotland’s Central Belt early in 1498 and Government Legislation to tackle the presence of the ‘Contagious Infirmity of Pestilence’ had been issued by the Council in Edinburgh in March of that year. Two months later the Aberdeen Authorities issued their own Regulations, which were specifically aimed at preventing ‘the Pestilence’. Perhaps due to advice received from Medical or Municipal Authorities elsewhere, Magistrates clearly understood that the Disease that now threatened was different from the ‘Strange Sickness’ the Town had faced ‘as before’ – surely a reference to the Great Pox – and therefore implemented different measures from those that had been decreed in April 1497. Since Plague had not actually broken out within the Burgh, the main concern was to prevent potential Sources of Infection from entering it in the 1st place. Residents were ordered to keep their Back Gates Shut and to strengthen any Walls surrounding their Property in order to stop ‘all Sickness & unlawful Folks’ entering. The 4-Entrances of the Town were to be Guarded constantly & Locked at night, and a Licence was required to Lodge Visitors.

It might be assumed that this was successful to prevent Plague from entering the Town as no more action was taken by the Council until the Summer of the following year, when once more the Entrances to the Town were to be closed and no-one was allowed to enter or leave without permission. Late in 1498, Authorities in Edinburgh had restricted Residents’ movements within the Town itself and had ordered schools, taverns and shops to close, an indication that sickness was actually present. In Aberdeen the fact that no such regulations were ordered makes it almost certain that plague had been successfully prevented. The following year, 1500, saw a particularly Virulent Epidemic sweep across much of Scotland’s Central Belt & Fife, but it is likely that Aberdeen again managed to prevent Plague within the City itself. Even though in August that year the Magistrates ordered 21-Inhabitants to be enclosed within their Houses for 15-days, this was most likely merely a precaution against possible Infection being Spread to healthy Residents rather than an indication that Plague was actually present. The Residents who were forcibly Quarantined had come into contact with People & Goods recently arrived in a Ship from Danzig (Gdansk, in modern-day Poland), where Plague had apparently broken out. The Crew of the Ship were also to spend 15-days in Quarantine and their Goods were to be burnt, a common method of ridding Items of Infection. No further action was taken against Plague, and by the time the Disease next threatened Aberdeen 6-yrs later, the Council had secured the Services of James Cumming as the City’s Resident Physician. Although it is a necessarily speculative contention, it could be argued that Cumming’s influence played a Role in the Authorities’ Decisive Reaction to Plague in 1506. Presumably responding to rumours of Infection elsewhere, they put in place the usual measures to prevent it from Entering the Town: the Official Entrances were to be Monitored, and Inhabitants were ordered to strengthen their Back Walls & Prohibited from Lodging Outsiders.

Additionally, extra Safeguards were imposed to Establish the presence of Infection at the earliest possible opportunity, with Residents ordered to declare any Sickness within their Household and to remain Housebound without receiving any Visitors if they did fall Sick. It is important to note that none of these Measures points to the actual presence of Plague within the City Boundaries. Rather, it shows the lengths to which the Council was prepared to go to prevent Infection from breaking out, even though such orders were both inconvenient and impractical. This is shown by the subsequent conviction of several residents for Lodging outsiders and buying in Wool from what the Council identified as ‘suspect Folks & Places’ in spite of the Threat of Plague. While there was no mention of the Council explicitly seeking Advice from Cumming, it might plausibly be suggested that the Physician’s Expertise was called upon the following year to tackle the renewed Threat of the Great Pox. It was termed on this occasion the ‘strange Sickness of Naples’, nomenclature used throughout the Continent, which suggests that the Aberdeen Authorities believed Soldiers participating in Charles VIII’s Campaign to be responsible for initially spreading the Disease. Magistrates ordered that all Sufferers were to undergo ‘Diligent Inquisition’ and that those found to be Infected were to stay within their own Houses & Yards, away from Healthy Residents, particularly Butchers, Bakers & Brewers. It is possible that, as a Trained Physician, Cumming would have carried out the Examination of suspected Great Pox sufferers. While Aberdeen had been remarkably fortunate to have avoided Plague for so long this was not to last, and it is possible to speculate that the Authorities’ delay in responding to the threat of Infection was at fault. Plague had broken out in Edinburgh in October 1512, but the Council in Aberdeen took a whole year to implement some of its usual preventative measures, which were limited to forbidding Strangers or Travellers from being Lodged within the City, ordering that Animals were to be Tethered and Decreeing that Communal Water Supplies were to be cleaned up (since Polluted or Stagnant Water was a particular Source of Infection). No specific Orders were declared for monitoring the Town’s Entrances, however & by April 1514 Plague was ‘ringing in all parts about this Burgh’. Remarkably, this was the 1st definite occasion in History that Plague had broken out within Aberdeen itself.

The 1514-16 Plague Epidemic

In spite of the presence of Plague within the City, the Council responded by passing Regulations that were mostly familiar and were designed to prevent further Infection from entering the Town from Outside. No Visitors ‘coming forth of suspect Places’ were allowed to stay without a Licence, and their Hosts were to Vouch that they were Safe, in other words, Free from Infection. A Local Government Official was to be told of any Visitor’s Identity. The Authorities were probably acting on past experience here, as Convictions during the threatened Outbreak of 1506 had taught them it was unrealistic to expect that no-one would be able to enter the Town unnoticed by the Watchers or that Residents would not secretly Lodge Outsiders despite Officials’ best efforts. The Council attempted to tackle this problem during the Town’s 1st Plague Outbreak by ordering that all Common areas and Passageways were to be secured, emphasising the necessity of ensuring Security at these most vulnerable Spots. Aside from this, it was also considered a priority to search Houses regularly in order to identify Residents who fell Sick. Legislation was also passed against receiving Goods & harbouring People from suspected Places, while Animals were ordered to be Tethered and Beggars were to be Banished (not least because they were often Visitors rather than being Native to the Town).

New Measures to Tackle Infection

Some significant developments also took place during the epidemic that showed how the authorities began to understand, perhaps due to Cumming’s advice, the importance of cleansing Goods & Quarantining sufferers. They also demonstrated that they were able to cope with more urgent circumstances brought about by the presence of Plague. It had previously been Council Policy that Infected Residents were enclosed in their Houses, but in 1514 Plague Lodges were built outside the Boundaries of the Town, on the Links area by the Beach. Residents who had already fallen victim to Plague and those who were suspected of being infected were sent there until they either Died or Recovered. Those fortunate enough to fall into the latter category were to remain in Quarantine for a further 40-days, and cleanse their own Clothes & Goods to remove any Infection. They would then be allowed to return to the Town. Once back at Home, they were to remain enclosed within their House for another 15-days before being allowed to attend Communal gatherings such as Church or Market. Despite these Stringent Regulations there was still a risk that they could be Infected, so they were forced, by a Nationwide Act of Parliament, to carry a White Stick for 20-days so that healthy Residents could identify (and, if they so chose, avoid) them.

In 1647 Bubonic Plague – broke out in the City, and killed around 25% of the Population. The Plague Epidemic that broke out in Scotland in the mid-1640s, particularly its effects on the City of Aberdeen where it remained Virulent from April 1647 until the end of the following year. The 1st to have struck the City for almost a Century. The surviving Council Registers and other primary sources show how the City’s Governors responded to the dual threat of Miasma & Contagion in well-established ways. John Paulitious was Edinburgh’s 1st Plague Doctor, but he died in June 1645 only weeks after beginning Employment. He was succeeded by George Rae.

An Epidemic of the Bubonic Plague, which had arrived in the South-east of Scotland towards the end of 1644, reached Aberdeen in April 1647. On the 7th of that month the Town Council ordered all Middens removed from the Town. On the 12th the Provost announced that the ‘Plague of Pestilence was Raging at Bervie’, 20-miles down the Coast. A 24-Hr Watch was appointed at Torry, the Bridge of Dee, the Blockhouse & all Entrances to the Town. Two weeks later the Plague ‘wes werilie instantlie expected to be neir our doore’, having been brought to the neighbouring Parish of Old Machar by a woman from Brechin. One of the 1st Local people to die was a child of the Woman’s Family who was known to have been attending one of the English (Junior) Schools in the Town, where he ‘had conversatione with the children of many of the inhabitants’. Recriminations began to fly. The Watch had not been ‘punctuallie keiped’, especially by those who sent a Servant in their stead, or some other ‘weake nauchtie persone’. Henceforth, a watch of 120-Armed Men would be deployed round the Clock, and anyone missing their turn would be fined £100. All Sturdy Beggars were to be ejected from the Town, cats & dogs killed, and ‘poysone laid for destroying myce and ratons’. No inhabitants were to attend the upcoming Fair at Ellon, and any contact at all with the Inhabitants of Torry or the Parish of Nigg would entail a £100 Fine. No Citizen of whatever Rank was to enter or leave the Burgh without a Pass from the Magistrates. Notification was to be given in to the Civic Authorities of any Member of the Household taken ill, ‘what seiknes soever it sail happin to be’, on pain of a £12-Fine. It was all too late. By the end of May the Town Council, most of whose Members had prudently retired to Lodgings in the Country, had ceased to Meet.

At the end of September it was still considered too dangerous to Convene in the City Centre & Council Elections took place at a Venue outside the Town at the Woolmanhill. Between the end of May & the beginning of December neither the Burgess Register nor the Register of Indentures listed any New Entrants. Church Services were suspended from September until January. The Visitation placed a huge strain on the Financial & Administrative resources of the Civic Government: at one point the Magistrates feared that unless some Emergency Funding was found quickly, ‘the Toun will be castin loose, and no ordour keipit at all’. Meanwhile the Sick & the Dying were removed to Temporary Huts set up at the Links and on the Castlehill, where they were looked after by a Team of 4 seemingly Immune ‘Cleangers’. When the end came many of the Dead were deposited in Mass Graves nearby – under, as the Treasurer’s Accounts reveal, 37,000 Turves. It must have been a wrenching experience to send one’s loved ones to the Camp on the Links, but as the crisis wore on it became a Capital Offence to conceal a Family Member’s illness. In December the Inhabitants were called upon to take all ‘uncleane, foull, or suspect’ belongings and to ‘wash, cleange, purge, expose, and put the same furth to the frost air’. By that point, however, the worst was over, and the Community was left to Mourn the loss of 1,700 lives, roughly 15-20% of the Burgh Population. Gordon Russell DesBrisay 1989

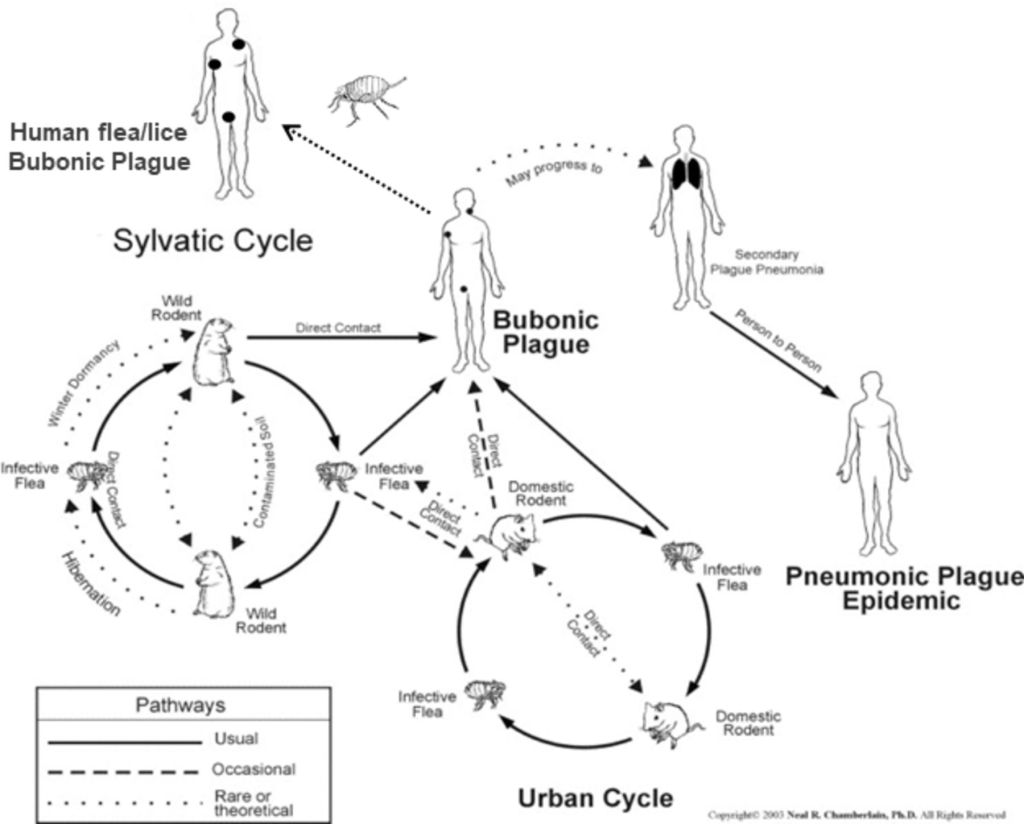

The real Cause of the Bubonic Plague was only discovered in the late 19thC: it is a Bacterium (‘Yersinia Pestis‘) carried by Rodent Fleas. Its discovery by Yersin & Kitasato involved the Scot James Lowson. Fleas get the Infection when biting Infected Rats. When an Infected Flea then bites Human Beings, it regurgitates a Blood Clot carrying the Bacteria into the wound. From there the Bacteria make their way through the human Lymph System. Plague Outbreaks have been contained since the discovery of Antibiotics, but they have not been eradicated. Recent Scholarship has postulated that Historical ‘Plagues’ might rather be attributed to an Airborne Virus transmitted Interpersonally, such as Ebola Virus, or an earlier form of Yersinia Pestis in combination with other strains such as Pneumonic Plague or Secondary Diseases such as Influenza.